(I wrote this post for the newsletter of my writing chapter, but thought you might enjoy it too.)

Technical innovation has recently evoked a huge change in the business of publishing as we’ve come to know and love it. The emergence of portals for digital self-publishing and the distribution of ebooks published through those portals directly to consumers has created far more choices for authors than was previously the case.

The kinds of authors who took advantage of these opportunities has been evolving, too. Originally, most authors who took the plunge into self-publishing were either unpublished authors or authors who had previously been published but were not actively publishing any longer. Authors who wrote for niche markets also were early to take advantage of this new opportunity. In the past year, however, more and more traditionally published authors have chosen to indie publish, either exclusively or in combination with traditional publishing. This decision mystifies many unpublished writers, particularly those who would like to be published by a traditional publishing house. As one of the authors who has made the choice to take some work indie, I thought I’d talk today about pros and cons of making that choice.

First, a little backstory. I write – or have written – under three names. I write medieval romances as Claire Delacroix and have published twenty-seven novels under that author brand. I also published a Claire Delacroix trilogy of apocalyptic paranormal romances set in a dystopian future. In addition, I’ve written four time travel romances and four contemporary romances, all of which were published under the name Claire Cross by Berkley. More recently, I have been writing paranormal romances and paranormal YA featuring dragon shape shifters under my own name, Deborah Cooke. EMBER’S KISS, coming from NAL in October, will be the eighth Dragonfire novel, the eleventh “Cooke-book” and my forty-eighth traditionally published novel in print.

My experience with traditional publishing is not unusual, so my reasons for going indie with my new Delacroix medieval are not unusual either. Let’s take a look at them.

1. Finishing What’s Been Started

This was the impetus that drove me to indie-publish my first original work. I like to write linked series, and I like to write long linked series. It’s not strategically a good idea to contract for (just for example) all ten books in a proposed series right off the bat. The hope is that the series will sell well, sales will grow and subsequent contracts will be for higher advances – which will mean more promotional budget and attention paid by the sales team to the books. Publishing houses also are leery of making such long commitments without having seen any sales numbers for the series in question. To contract incrementally – maybe three books at a time – makes sense both for the author and the publishing. Incremental contracting of a long series, however, does leave the door open to the possibility that the publisher and author might part ways before the series is completed. This invariably has meant that the series would not ever be completed, as traditional publishers do not like to pick up a series that has been started at another house. If they’re interested in publishing the author, they’d rather have something new that can be entirely their own.

My last two traditionally published Delacroix medieval romance trilogies were loosely linked. The Rogues of Ravensmuir (THE ROGUE, THE SCOUNDREL and THE WARRIOR) was followed by The Jewels of Kinfairlie (THE BEAUTY BRIDE, THE ROSE RED BRIDE and THE SNOW WHITE BRIDE). The second trilogy features a younger generation of the same family. There are eight siblings in the family at Kinfairlie, and I was expecting to write another five books after The Jewels of Kinfairlie trilogy. Unfortunately, the market for historical romances was not very robust in 2005, so the publisher and I parted ways. It was subsequently impossible to place the rest of the series with any other traditional publishing house. Rather than pitch a different medieval series at that time, I chose to do something completely different. I wrote the Prometheus Project (FALLEN, REBEL and GUARDIAN), that Apocalyptic paranormal romance trilogy mentioned above, and just loved writing those books.

Readers can be a faithful bunch. I have been hearing from readers since 2005 that they’re waiting for the other Kinfairlie sisters to have their stories told. (Only one reader has asked about the two remaining brothers. I’m not sure why, but there you go.) This has troubled me. I think it is critical for an author to keep the faith with his or her readers, and one part of doing that is to finish series once they’re started. With traditional publishing, though, this has not always been possible. Indie publishing gave me the opportunity to continue the Kinfairlie story: I indie published THE RENEGADE’S HEART, the first book in The True Love Brides series, last week. This was very satisfying for me. I loved returning to my medieval world and taking the next step in bringing that series to completion.

2. Exorcising Ghosts

This reason is a variation of the first one. In the process of placing those forty-eight titles, I’ve pitched a lot of story ideas that did not ultimately sell. Some of them have been vague ideas (of the scratched-on-bar-napkin variety) while others have been full written proposals. The latter would probably make a three foot stack of paper if gathered together and piled up. The problem is that the ideas which have been more fully developed haunt me, much like those unmatched Kinfairlie siblings. (I can forget bar napkins, apparently.) Some of the story ideas and characters I really, really like – which is why I have still have those proposals stashed away.

Typically, when an author is in a relationship with a traditional publishing house, any idea during the option process but is not contracted by the house disappears forever. Because the idea has been rejected, it’is not new or fresh or even worthy of consideration in subsequent discussions. There are exceptions, of course, but in a very real sense, traditional publishers have controlled not only what is published but what is not published: when an author presents ideas at option, the one that is ultimately contracted will be written and published. The others will fade away. By the time the author is up for deal again, he or she will have a crop of new ideas or the publisher will be looking for different kinds of ideas.

It’s always been possible for an author to walk away from an option offer to write “the book of his or her heart”, or to work on that book on the side, but for many working writers like myself, that just hasn’t happened. I’ve not been alone in making a deal where I could and moving forward from that point.

The issue is that some of those ideas are as persistent as faithful readers, and haven’t faded quietly away. I have probably a dozen ideas that pester me to write them down, and I think that’s pretty typical for writers. It might be that those ideas were not the right ideas at the right time, but that doesn’t mean their time can’t be now. It might be that those ideas were a little bit too different for traditional publishers, but that doesn’t mean they’re too different for readers. It might be that the idea was outside the bounds of what the editor considered to be my brand, but that doesn’t mean that readers won’t agree. (After all, I don’t.) In traditional publishing, there hasn’t been a good or an easy way to discover whether those editorial judgment calls were right or wrong.

Now there is. Indie publishing is a place to give voice to those persistent story ideas.

3. Pushing the Boundaries

Traditional publishing tends to be conservative about editorial content, particularly in the romance genre. There are often concerns from editors about stories that don’t cohere to an established idea of what is effective in a specific sub-genre, or stories that don’t include expected elements, or stories that challenge expectations in some way. It is always difficult to see a book published well that pushes the boundaries, or one that hybridizes genres or subgenres.

I know this because many of my book ideas fall into this category. The problem is that it’s impossible to know what readers will make of a book before that book is published. The other problem is that I don’t believe for a minute that readers are as conservative as editors tend to believe readers to be. For example, I have consistently added paranormal and fantasy elements into my medievals, and had to fight for their continued inclusion in the final book. Is it really true that readers don’t want to read historicals with paranormal elements? I find that hard to accept, especially in a market that is so hungry for contemporaries with paranormal elements as our current market. THE RENEGADE’S HEART is a paranormal medieval, as will be the other books in The True Love Brides series. I really enjoyed populating the paranormal realm in this book and taking some chances. We’ll see what readers think of that.

What’s important to note here is that the model of indie publishing is so different from that of traditional print publishing that both the editor and the author can be right in any given example. Digital publishing is very well-suited to works that may appeal to a niche market, while traditional publishing – particularly in the romance genre, which tends to be published in mass market originals – does not service niche markets so well. There are two main differences to account for this: the sales cycle, and the financial model.

The sales cycle in traditional publishing is derived from the reality of physical book distribution. Any given bricks and mortar book store has a specific amount of shelf space. Publishers release books monthly (or even more biweekly) to best exploit that physical space. Because physical books will be removed to make space for new releases, a print first book has a window of opportunity of two to four weeks to perform. Indie publishing relies more upon digital editions of books, which do not consume physical space. A digital book can wait on a server forever to be discovered. A digital book can have a very different sales cycle than a physical book, at very little incremental cost of ensuring its ongoing availability. Because of this, digital publishing can offer more opportunities for long-tail marketing. Indie publishing also tends to use print on demand technology for physical books and this echoes the long tail advantages of digital books – the POD file waits on a server until a customer buys the book, then the book is made “on demand”. There is no inventory cost for physical books, no warehousing required, and no returns.

Then there is the different financial model. Consider the possibility that there are some people who want to read paranormal medievals. Let’s speculate that there are 10,000 of them in the United States. If my paranormal medieval romance was published traditionally, the primary focus for format would be the mass market paperback. Although there are variations depending upon the individual contract terms, we can take fifty cents as an average royalty per unit sale for the author: if 10,000 units were sold, the author would earn out $5,000. No one would be very excited about this kind of sales history. It is a “meh” result. In contrast, indie royalty rates are much higher, primarily because indie publishing tends to focus on the digital book format. If the indie published edition of that book was priced it at $4.99, royalties would be in the vicinity of $3.50 per unit. Selling those 10,000 copies would earn the author $35,000, a sum that most authors would find far more interesting. It might be a number that made writing the book worthwhile for the author. Of course, there are costs associated with indie publishing and no guarantees that the target audience can be found, but still indie publishing can serve niche markets more effectively.

4. Proving Marketability

The final reason I offer for a traditionally published author to go indie is that of proving the existence of audience. Traditional publishers rely upon accumulated sales data for an author who has been previously published, in order to decide whether to publish that author again in the future. This is primarily Bookscan data, which is point-of-sale data for print books. Authors thrive, survive or die – metaphorically speaking – on the basis of the sales numbers for their most recently published work. A book that “doesn’t perform” can condemn an author’s career, or at least hamper it. In traditional publishing, the “way back” often involves a new and different idea, maybe in a new and different subgenre or genre, maybe with a new author brand.

But what if that last book wasn’t published well? It might have had a mediocre cover. What if the timing of the book’s release affected its sales? World events influence book sales overall and individual books get caught in the crossfire. I have a backlist book that was originally published shortly after 9/11. There were virtually no fiction sales for 90 days after that horrible incident so every book published in that timeframe failed to perform. Some of them got second chances but most didn’t. What if it was the publisher that failed to perform, not the work itself? There is an old saying in publishing that if an author isn’t being published with enthusiasm, that author is better off not being published at all. With the changes in the publishing market in the last decade, a far higher percentage of traditionally published authors are being published without enthusiasm.

Some of the first authors to test the waters of indie publishing were previously published authors who were no longer being published. Many of these authors had been published by traditional publishing houses in the midlist. Most of those authors entered the indie publishing forum by republishing their backlist titles, as I did. Most of those authors believed their backlist books deserved a second chance. They all believed they could market their own books better than their publishing partners had marketed them – a great many of those authors were proved to be right and established new careers for themselves. A second chance for an author brand or an individual book is an opportunity prove that an audience exists for the work.

Is there a market for Claire Delacroix paranormal medieval romances? I hope there is, but I don’t really know. The good news is that now there’s a way to find out for sure. Indie publishing such a book, as I have just done, provides an excellent opportunity to get results instead of making guesses.

So, there are four reasons to go indie, even for an established and/or traditionally published author. The thing is that I don’t believe it needs to be an either/or decision. There’s a lot of rhetoric in author circles these days about choosing indie publishing or traditional publishing to the exclusion of the other model, but both models offer distinct advantages to authors – and also to publishers. It seems only reasonable that both models can be used in tandem to both build author brands, to explore niche markets, to test the marketability of unusual books, or give works a second chance. Indie publishing is a new tool and one that can open many doors for authors. That’s pretty exciting stuff.

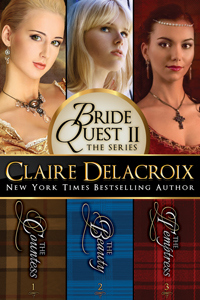

The Bride Quest II Boxed Set includes all three full length medieval romances in that linked trilogy – The Countess, The Beauty and The Temptress. It’s usually $8.99 but is $4.99 this week at Amazon, Apple and Barnes & Noble.

The Bride Quest II Boxed Set includes all three full length medieval romances in that linked trilogy – The Countess, The Beauty and The Temptress. It’s usually $8.99 but is $4.99 this week at Amazon, Apple and Barnes & Noble.

This digital boxed set includes all three full length medieval romances in this trilogy. You can read excerpts from the individual books in the trilogy,

This digital boxed set includes all three full length medieval romances in this trilogy. You can read excerpts from the individual books in the trilogy,