Last week, we reviewed the sales numbers of my two Bride Quest trilogies, one of which is still being distributed by Random House and one of which has been re-published in new editions by me. I mentioned last week the differences in sales patterns in digital books released by indie-authors as compared to those from traditional publishing houses. Today, we’ll talk about that.

We have a perfect point of comparison here. I wrote two medieval trilogies, the Bride Quest I – to which Random House still holds the rights—and the Bride Quest II—to which I hold the rights. All six of these books were published roughly ten years ago in mass market editions and subsequently (in 2009) published in digital editions. These books are on level ground in many ways: they’re in the same sub-genre; they’re published under the same author brand; they have the same tone; they have a similar premise; they are even linked to each other; they were packaged and published similarly; they sold at very similar levels when originally published.

We have a perfect point of comparison here. I wrote two medieval trilogies, the Bride Quest I – to which Random House still holds the rights—and the Bride Quest II—to which I hold the rights. All six of these books were published roughly ten years ago in mass market editions and subsequently (in 2009) published in digital editions. These books are on level ground in many ways: they’re in the same sub-genre; they’re published under the same author brand; they have the same tone; they have a similar premise; they are even linked to each other; they were packaged and published similarly; they sold at very similar levels when originally published.

And here’s our point of comparison: there were digital boxed sets published for the first time last year for both trilogies. On June 25, 2012, Random House published a digital boxed set of the Bride Quest I. On March 12, 2012, I published a digital boxed set of the Bride Quest II. The sales patterns for 2012 for these two bundles present an excellent opportunity for comparison.

The results might not be what you expect. RH’s bundle was priced at $14.99. (Even more astonishing, the library edition was $71.91!) My bundle was priced at $4.99 for 2012. Raw sales units for June to December 2012 were 547 for the RH bundle and 900 for mine. Not so much difference there, but the difference that exists can probably be attributed to the price point.

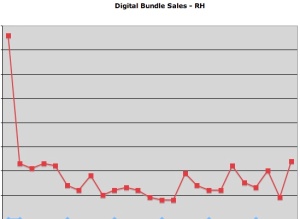

What’s more surprising is the pattern of sales. First up, the sales chart for the RH bundle:

I have weekly sales data from RH, which shows the sales pattern quite clearly. A huge chunk of the sales for the RH bundle were made within two weeks of the on-sale date. Sales of the bundle spiked and dropped. This pattern is characteristic for sales of books from traditional publishing houses, regardless of format. An editor once told me that 80% of any book’s sales are made in the first 14 days that it’s available for sale. That’s why all promotional efforts are focused on the on-sale date, when the book is supposed to make a big splash. That’s why no one in bookselling cares that mass market books are stripped of their covers and removed from the stores in 2 to 4 weeks. Essentially that title’s moment in the sun is over and it’s time to move on to new releases.

This sales spike is supported by the mechanisms available through online bookstores. Because publishers like to build as big a spike in sales as possible on the on-sale date, online booksellers allow customers to pre-order books in either digital or print format. The sales that are gathered in advance are all processed on the on-sale day, counting as sales for that day even if the customer placed the order six months before. A big advantage of this system is that consumers can’t forget to buy a book when it comes out: they just order it when they think of doing that. Currently, it’s only possible for indie authors to list a book for pre-sale on KOBO and that’s a new capability. It might very well be that indie book sales would show more similar patterns to books sold by traditional publishing houses if we could set up for pre-orders—or not. We won’t know for sure until that capability is available on other portals.

Sales of my bundle take a different pattern. Here’s my sales chart:

Now, I only keep monthly sales data, but in a way, that’s not too important. My sales don’t show those kinds of radical highs that are characteristic of traditional books being promoted on their on-sale dates. Sales are fairly consistent with little wiggles and a gradual ascent.

Let’s look more closely. There are a bunch of things happening in this chart simultaneously. First, let’s look at that initial leap in sales – it’s not a spike but the beginning of a climb, and it’s not a coincidence that it happens in June. There are two contributing factors to that jump in sales numbers. First of all, I had put The Countess into the KDP Select program at Amazon in March. That program requires a 90 day exclusive with Amazon for the title in question. As a result, the BQII boxed set (which included The Countess) could only be distributed to Amazon during those 90 days. The exclusivity period ended in the middle of June, and I immediately published the bundle to other portals. The thing is that in June of last year, I was still using Smashwords to feed to all other portals. In June, BQII was still waiting in the line for approval for that distribution and very few units sold directly through Smashwords. The extended distribution is more of a factor in the sales growth of July and August, when BQII became available for purchase at the other portals.

The main factor driving that June leap is the publication of BQI. There’s an old saying in publishing that frontlist sells backlist. In this case, BQI acted as frontlist because it was the new release. The visibility of the new publication (such as it was) increased demand for the linked series, BQII. That makes sense.

There’s one more factor that is shaping these results: all of my medieval romances took an uptick in June of last year. Nothing happens in isolation when you have a broad and deep backlist like mine – that last factor was the promotion of another Delacroix medieval romance. The Beauty Bride, book #1 of the Jewels of Kinfairlie, was free for the first time in May. The ripple effect from that promotion is still shaping the sales of my medieval romances, but we see the uptick in both BQ’s in June, quite possibly influenced by the raw numbers of people reading TBB. It’s also possible that the publication of The Renegade’s Heart in May, my first Claire Delacroix medieval romance published since 2005, also increased visibility for both digital bundles.

Finally, let’s compare the overall sales patterns for the boxed sets.

The top line with the red dots is sales of BQII, the one managed by me. The lower (and shorter) line with the yellow dots is BQI, managed by RH. There is a little goofiness in compiling the RH data into monthly numbers because their bundle went on sale the 25th of June – those June numbers are only for one week. If we gathered the first four weeks together (1 in June and 3 in July) instead of compiling by calendar month, the spike would be emphasized more than it is here.

We can see that the sales for indie-pubbed bundle are wavering their way to growing over time, instead of spiking and dropping. There is no similar focus on the on-sale date. The differences are interesting.

On the one hand, this is a function of online book sales. The algorithm at each online retailer learns more from every single sale of a given book. It builds data on an ongoing basis—data like “people who bought A also bought B” and “people who read Author A read Author B”—then can make better recommendations to shoppers. It takes a lot of data to find patterns and the more data there is, the more accurate the system’s recommendations will be. Because a new digital release has no data (i.e. there was no BQII boxed set available in any format before my publication of one), it’s very common for an indie release to have to rouse itself from flat-line sales. Over time, the accumulation of sales data makes the algorithm more effective. It suggests the book to more shoppers and gets it right more often. It’s common in indie publishing to see a snowball effect over time, and to see sales continue to grow for digital books. This is called long-tail marketing.

The thing is that both of these bundles were digital-only and both of them were new titles. Why did the RH one sell so differently? You can see on the chart for RH that the same pattern of increase thanks to the algorithm is asserting itself a little bit but not as vigorously as with my bundle.

With over 50 titles published traditionally, I’ve seen the spike-and-drop sales pattern 50 times. Every single book’s sales have adhered to that pattern. Sales dribble along after the drop, and usually there’s an increase when a new title in that series or under that author brand is published. The shape of the curve is completely predictable, even if the size of the original spike isn’t. On the other hand, I have about 25 titles indie-published, and their sales patterns range from steady sales for some titles to fairly erratic ups and downs on others. There are a number of sales patterns on my indie books—except for spike-and-drop. It’s the one pattern that none of my indie titles show. I think that’s weird. They also all show a gradual increase in sales over time—the gross sales may not grow month by month, but they certainly grow year by year. That’s never been what happened with my traditionally published books.

Prior to this little exercise, I had attributed the difference to the fact that my indie books are primarily digital releases, although they are simultaneously available in POD, while my traditionally published books had been primarily mass market originals, although for the past 6 years or so, they’ve been published in simultaneous digital editions. This example, though, shows that’s not the case. Both boxed sets were new releases and digital only. Certainly, the fact that indie authors don’t have the ability to set a title for pre-order is a factor in not seeing that sales spike, and another is possibly the fact that most of my indie titles are republished backlist.

I have a feeling there’s another variable, though. It could be an effect of pricing. It could be that results are being shaped by assumptions—because assumptions are determining other marketing choices. It could be something entirely separate. I’m going to keeping an eye on the sales curve for my upcoming indie original titles, to see how they shape up.

As you might have guessed, I have a Theory to test.

Have you factored in the digital book cover displays. Personally I like yours better than the traditional publisher’s presentation. As a traditional book buyer I am influenced by the cover art and I guess that does translate to the digital appeal for me although I do shop on line with covers off mostly.

LikeLike

Thanks for commenting, Kat – I don’t know how to quantify cover art, but I believe you’re right. Cover art is a big factor in my book buying decisions, independent of the format.

LikeLike